The Illusion of Control: Does Interactivity Make a Story More Engaging?

In the late 1970s, a computer game called Colossal Cave Adventure became the first-known work of interactive fiction. Since then, video games have always — inherently — been about making choices. But deciding whether to A) jump over, or B) duck under, a projectile feels relatively low-stakes compared to sculpting a character’s relationships, moral compass or identity. When a decision holds moral weight, it’s no longer just a reaction. Instead, players must consider consequences that extend beyond the immediate moment.

But does this illusion of control allow for a more engrossing narrative experience? The folks over at Netflix think so. After releasing a few interactive programs aimed at kids, the streaming platform doubled down, launching an interactive, one-off episode of its Black Mirror series called Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018).

In Bandersnatch, Stefan, a fledgling programmer, works tirelessly on a text-based computer game with a branching narrative. (Think choose-your-own-adventure novel, but with more typing.) As he programs more paths, Stefan struggles with his own mental health and becomes consumed by the idea of free will.

This meta-dissection of the illusion of control amplifies intriguing questions surrounding the rise of interactive storytelling, both in games and cinema. Namely, does being actively implicated in a narrative experience make said experience resonate more deeply with the participant?

Narrative-Driven Games Emulate Cinema

Innovations in technology allowed games of the late 1990s to break new narrative ground, as seen in titles like Metal Gear Solid (1998), Silent Hill (1999) and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998). Of all these epic, narrative-driven games, one stands out: Square’s 1997 role-playing game (RPG), Final Fantasy VII (FFVII).

More “hardcore” than your run-of-the-mill mainstream platform, FFVII became the first game of its kind to gain mass-market appeal outside of Japan. The game had it all: unforgettable characters, complex world-building and mythology, boundary-pushing graphics and a cinematic score. The three-disc PlayStation epic took a then-unprecedented 100-person team about three years and $80 million to complete.

For the majority of FFVII, the player controls Cloud Strife — a soldier-turned-rebel with a nebulous backstory and a severe case of amnesia — whose tendency to be an unreliable narrator has since placed the game in conversation with Fight Club (1999) and Memento (2000). Video game critic Patrick Holleman wrote that no story had “ever deliberately betrayed the connection between protagonist and player like FFVII does.”

In part, this was so resonant because, at the time, FFVII was compared to an interactive movie. When the player, who had essentially become Cloud, was betrayed by him, that feeling of loss and confusion was underscored by the narrative’s interactivity and the way in which the player had become complicit in the lie.

Rebelling Against Linear Narratives

However, games like FFVII were still critiqued for being linear. Apart from a few side missions, the narrative followed a single, predetermined path with little room for player choice. With the release of Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto III (GTA III) in 2001, the pendulum swung in a new direction. Instead of emphasizing control, GTA III aimed to give players freedom — and the tools to harness it.

Sure, there were memorable missions and characters, but there wasn’t an in-your-face narrative thrust, and that “open-world” quality was much-loved. However, GTA III‘s success didn’t signify a complete paradigm shift: Some gamers still equated epic, engrossing stories with linearity. This paved the way for games like BioWare’s Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (2003) and, later, Quantic Dream’s Heavy Rain (2010) and Telltale’s The Walking Dead (2012).

While these entries vary in terms of genre and gameplay, they’re linked by the way they combine linear storytelling — there’s a narrative thrust and obvious endpoint — with the freedom to choose — you can create a context that surrounds the linear narrative. Whereas FFVII tried to make you forget you were playing a game, these titles embraced the things that separated them from movies. Namely, they aimed to put players in the driver’s seat.

Both BioWare’s shooter-RPG Mass Effect (2007) and Bethesda’s action-RPG Fallout 3 (2008) blend GTA III‘s open-world, non-linear experience with a strong central narrative. In both games, the narratives branch out from a central plotline, allowing the player to create a unique protagonist and shape distinct relationships with other characters. Whether you’re part of a gigantic space opera or roaming an apocalyptic wasteland, the ways you treat other characters — and the moral (or immoral) actions you choose to take — contextualize the game’s narrative.

And this raises the question: Does a player’s illusion of control end there — as mere context?

The Bandersnatch Parable

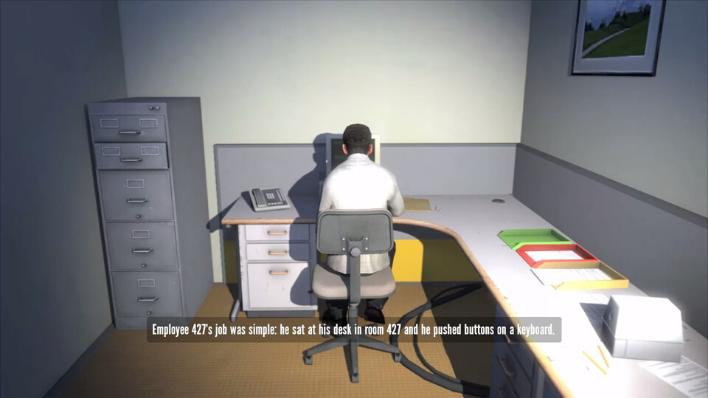

Both Netflix’s Bandersnatch and a 2011 game called The Stanley Parable are meta-attempts to understand the role of predestination in interactive stories. Both titles wonder how much — if any — control players actually exert over a narrative. In The Stanley Parable, there’s no combat or action-based sequences. Instead, the player searches a surreal office environment, choosing to either adhere to what the narrator says the titular character will do next, or rebel.

In Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror series, the writer often confronts the ways technology impacts society — these intersections between the real and the virtual (or imagined). Bandersnatch is no different. At crucial moments during the episode, viewers must choose Stefan’s next move while a timer counts down. There are five different endings, and within each of those main endings, more, very nuanced outcomes branch off. In one of the variants, Stefan sees “behind the curtain” and discovers that someone — you, the Netflix viewer — is pulling his strings.

Interestingly, while The Stanley Parable was heralded as a landmark self-referential narrative, the Emmy-winning Bandersnatch was maligned by critics for feeling too “gimmicky.” Essentially, Bandersnatch is a series of alternate endings (popularized way back in 1995 by the Super Nintendo hit Chrono Trigger). Sure, it’s fun to see where the rabbit hole leads, but the derivative, meta nature of the plot keeps reminding us that the control is an illusion, and that the outcomes are all predetermined.

So, why this push toward interactive narratives if it’s all pre-ordained? In tracing (albeit briefly) the way narratives in games have developed over the last few decades, there’s no denying that we — as players and viewers — take pleasure in being part of the thing that’s unfolding. If we’re implicated, the stakes feel higher, and, if the stakes feel higher, we’re not just going through the motions. By forcing a particular outcome, you can voicelessly assert your position — a stance or desire. Even if, deep down, you know that’s all just part of the game.